The widespread use of facial recognition technology is almost upon us. The new iPhone is available with FaceID where you can unlock your phone with your face.

Facial recognition is not new. It?s been a sci-fi staple for decades, and its practical roots are in the 1960s with Palo Alto researchers on RAND Tablets manually mapping out people?s features. Even back then we could give a computer enough data to be able to match a person to a their photograph. The group, led by Woodrow William Bledsoe even managed to calculate a compensation for any tilt, lean, rotation and scale of the head in a photograph.

Data inputs stayed pretty rudimentary, with manual input of details being replaced by the Eigenfaces in the ?80s and ?90s. This would be the start of computer vision systems leveraging the kinda freaky power of big data.

Our ever-increasing ability to process huge amounts information underpins the advances we?ve seen in the last few years. Today, facial recognition has scaled from unlocking phones to tracking criminals. Cameras at a beer festival in Qingdao, China, caught 25 alleged law-breakers in under one second. This sort of efficiency guarantees the technology could go mainstream, and in turn, be exploited. It probably makes sense to pause and ask: where can it go wrong?

Earlier this month, reports emerged that Samsung?s Note 8 facial recognition feature could be tricked by photos of the person?s face. Hopefully, Apple?s is less spoofable. What can happen when we combine the large amount of facial biometrics data with a potentially imperfect system? What sort of societal implications would there be if you were recognized by someone, anywhere and everywhere you went? Gizmodo connected with experts in law, technology, and facial recognition to find out.

Joseph Lorenzo Hall

Center for Democracy & Technology?s Chief Technologist in Washington DC

Like all biometrics, facial details are not secret and can?t easily be changed. And privacy enthusiasts can?t engage in self-defense such as covering your face (in most cultures). That means that biometrics are not a full authentication factor since they?re often easy to capture and spoof (even fingerprints for phone unlock have to fall back on something secret like a passcode). So, if these systems don?t include ?liveness? checks, it?s conceivable that a decent image of someone?s face could be used to gain unauthorized access.

It?s pretty easy to match facial patterns against public data and we?re certain to see systems that allow submitting of a facial pattern through an API to get basic details and then a la carte data broker data (these systems exist now for identifiers like email). I would not be surprised to see dark web services in the future offering details about people based on facial patterns (imagine if a criminal is casing a locale for a robbery… They would probably love data that indicates which security guard has a home mortgage under water and more susceptible to influence and facial pattern would be very easy to capture remotely.)

What can tech companies do before implementing facial biometrics?

Depends on the application. If they merely want to measure for traffic in a store or demographics of an audience, they don?t need facial feature identification. If they are using it for biometric unlock or authentication, they should store the facial pattern in a secure format (just like we don?t store passwords, but hashes of passwords, never should raw biometric data be stored and/or transmitted.) Ideally, one could opt out entirely of using this feature.

Woodrow Hartzog

Professor of Law and Computer Science at Northeastern University

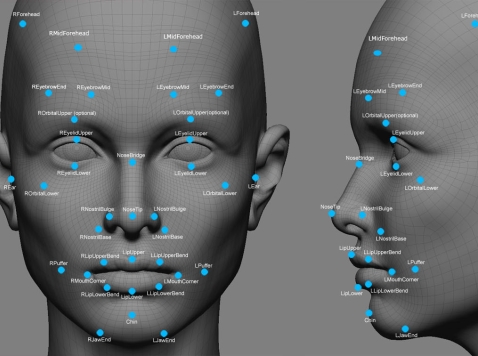

In short, facial biometrics are dangerous because there are few rules regulating their collection, use, and dissemination even though they are capable of causing real harm. Faceprints, which are the maps that power facial recognition technologies, are only specifically addressed in a few laws and regulatory schemes. Some cities and states have restricted when facial biometrics can be collected and used. But generally speaking, unless one of these limited and specific rules restricts industry and government from deploying facial biometric systems, they are largely fair game. Images of our faces can be captured, stored, and compared against a database of faceprints, which grow larger upon use.

Much of the risk from biometrics is created by how they are implemented and the design of the technologies that use them. For example, will the faceprints be stored locally and can authentication occur without having to access a remote location using the Internet? Or will they be stored in a centralized database? If so, what are the technical, administrative, and physical safeguards for those databases?

If a database of faceprints were compromised, it would have a ripple effect on authentication systems that used the faceprint, as well as possibly allow unauthorized parties to make use of the faceprint for surveillance. We?ve already seen some instances of facial recognition software being weaponized as a stalking tool. People, governments, and industries might be tempted to comb through social media feeds and photo databases using hacked faceprints to locate people in a much more efficient and dangerous way.

Christopher Dore

Partner at Edelson PC law firm in Chicago where he focuses his practice on emerging consumer technology and privacy issues

Facebook has the largest database of recognition data in the world, period. Maybe the NSA has more. Maybe they don?t at this point. But when you have a situation where a company is holding a database of that type, there are a lot of concerns that come up. What are they going to do with it? Right now, Facebook outwardly is using it for something fairly innocuous which is the tag suggestion feature. But they?re sitting on a huge resource in terms of what that is, and they could start using it for other products.

If a company has this huge facial recognition data and they can go to a retail chain and say hey we can backend your security surveillance system with our facial recognition database and you will have an unbelievable sense of who is coming in to your store. And from a service level that is frightening but it?s maybe just being used for marketing purposes, but then it can get to a more nefarious place. You know there?s all these online companies that do mugshots?

You could get a database from one of them and start using that to say that you?re scanning for criminals but those mugshots are only people that are have been arrested. They haven?t actually been convicted of anything.

I will say the further down layer to this, is that recognition has gotten very good. But it is not perfect and the instances where it is less than good is dealing with minorities. African-Americans have the hardest time accurate identification. When you take what I?ve said about databases and mugshots and all that data that?s being put together, you have a very high-risk of misidentification and discriminating against people.

About The Author

Bryson Masse